How SAIT students plan to save the environment and reduce industry costs with the Innovative Student Project Fund

Year-round, SAIT’s Applied Research and Innovation Services hub helps SAIT students get financial support for creative classroom-based capstone projects with real-world impact.

The Innovative Student Project Fund (ISPF) helps students address burning questions (like “What if a spider web is collecting more than bugs?”), explore lightbulb moments (like how technology could make your daily commute more efficient) and improve the quality of life for living things big and small. Some students even work with industry sponsors who can benefit from their findings.

To receive funding, students must write a proposal and pitch to a panel of experts from across SAIT. The process encourages innovation, puts students in an entrepreneurial mindset and helps them demonstrate their innovative leadership.

Five projects have received ISPF funding for the upcoming semester, and their projects address everything from the buildings we live in, the cities we commute in and the province we call home.

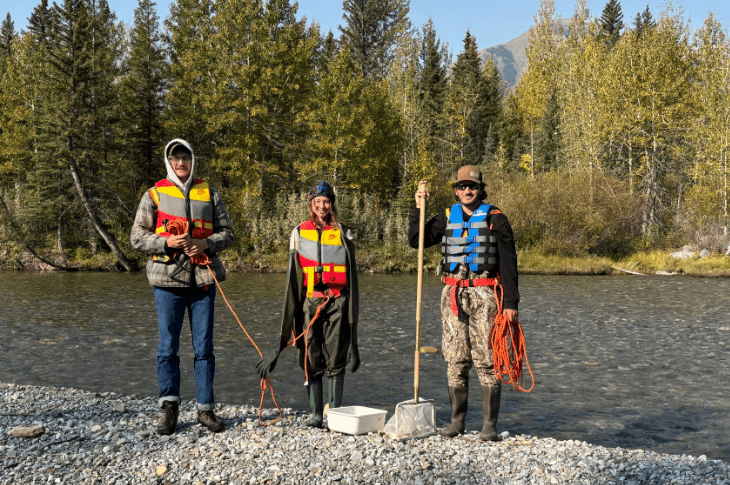

Keeping river fish populations healthy with environmental DNA

Have you ever seen a fish chasing its tail? Dogs — yes. Fish — hopefully not.

When a fish chases its tail, it can be a symptom of whirling disease: a fish illness caused by parasites that use river sludge worms as a host. It can be lethal to fish and, once in waterways, hard to trace and manage. It’s often spread when humans travel between water bodies without properly washing their equipment.

To preserve the ecological integrity of these recreational spaces and provincial parks, this group is using environmental DNA (eDNA).

What is environmental DNA (eDNA)?

Environmental DNA is an emerging technique that captures species cells left in the environment and processes them in the lab to extract, isolate and sequence DNA for comparison to reference databases. It allows the identification of species in the environment without directly capturing the species of interest.

Using samples from the Kananaskis rivers and lab analysis, the group hopes to detect the sludge worms and parasite species (Myxobolus cerebralis) that lead to whirling disease — ultimately identify whirling disease before it decimates the local fish populations.

ISPF is helping the group navigate the costs of this emerging technology.

“The sequencing of eDNA requires expensive specialized reagents, so around 75% of our funding will be going towards those reagents,” explains Luke Vadeboncoeur from the project team. “The remaining funds will be used to purchase eDNA extraction kits and to cover travel costs to collect more field samples.”

The group also has access to the eDNA lab at SAIT.

“Our mentor for this project, Colin Pattison [Instructor, MacPhail School of Energy], is supporting us throughout the process of collecting, extracting, sequencing and analyzing our eDNA samples.”

Bonus: Glimpse into a day-in-the-life of an integrated water management student

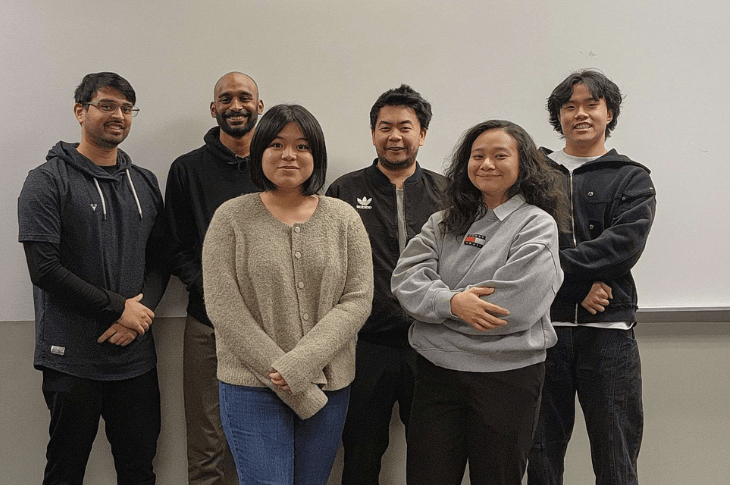

Using the fine trap of spider’s silk for wildlife monitoring and conservation

If you’ve ever taken a walk through a wooded area, you’ve more than likely ended up with the slightly sticky sensation of a spider web on your face. But before you freak out and claw the silky strands away, consider this: there could be some interesting data on those suckers.

Traditional methods of monitoring wildlife — camera traps, live capture, observation — are often expensive, time consuming and used only to track elusive or rare species. Here in Alberta, with our vast landscapes, this can mean data is slipping through our fingers. Species facing conservation challenges can be difficult to detect, and invasive species can affect wildlife populations before we know it.

So how are spiders going to save them?

This group is finding out how spider-web eDNA can be used as an affordable, non-invasive and scalable approach to biodiversity monitoring to support conservation. Webs trap more than just flies. Webs can catch traces of all kinds of terrestrial vertebrae — including small and large land mammals, even those travelling in small groups.

“The ISPF funding will help cover essential lab costs for analyzing the DNA collected from spider webs, including extraction materials, PCR reagents and sequencing. It will also support fieldwork travel for sample collection,” the project team — Nuttakan Chimpanid and Tzu-Yum Hsueh — explains. “This makes it possible for us to test spider-web eDNA as a low-impact method to monitor large mammals in Alberta.”

Like their peers studying whirling fish disease, they also have SAIT’s eDNA lab at their disposal, and the guidance of their faculty advisor and project sponsor Colin Pattison.

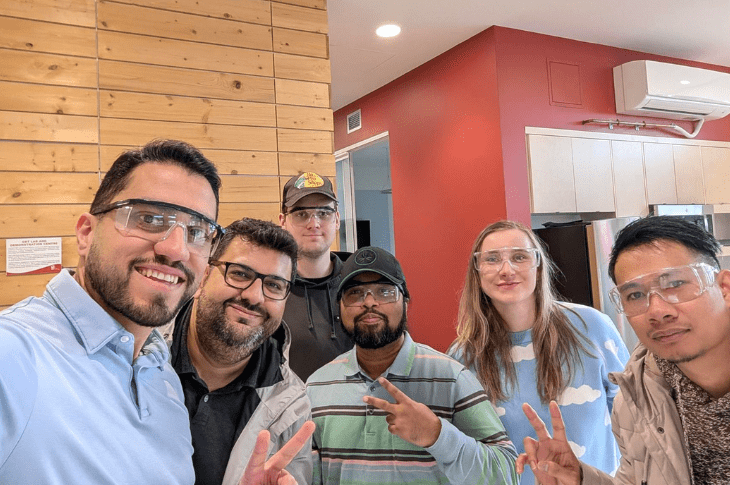

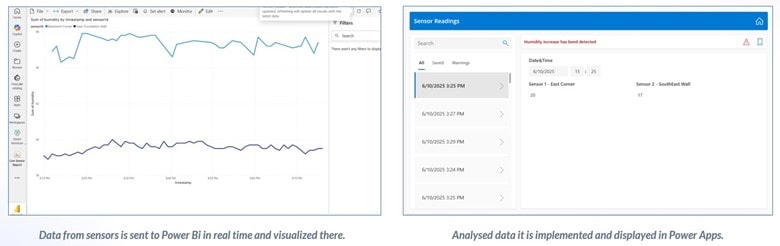

Monitoring moisture levels in the home from your pocket

Homeowners, beware! Unexpected leaks in homes or buildings can lead to hidden moisture buildup, causing structural damage, mold growth and costly repairs if left undetected.

Many monitoring solutions only detect obvious flooding — as if you didn’t notice your carpet was soaking — or are costly, leaving a gap in affordable, reliable early detection systems.

This group is developing a low-cost, real-time moisture monitoring and alert system, which would detect abnormal moisture levels through sensors, send real-time mobile alerts to homeowners or property managers and allow for remote monitoring.

ISPF is helping the group be flexible and explore options for their projects. So far, Sayed Azher Mahmud tells us, they’ve used some of their funding to purchase humidity sensors.

Many of the things they need are being provided by SAIT.

“Our instructor Shawn Simlik has been helping us stay on track with his feedback, and his follow-ups and suggestions are beneficial,” Sayed also mentions, “We also had the privilege to visit the SAIT Green Building Research Centre, which was really insightful, and we were able to exchange some ideas with Maeric Rico [a Laboratory Technician with SAIT’s Applied Research and Innovation Services Hub].”

Addressing traffic congestion through the power of artificial intelligence

Here’s something most drivers will be very familiar with: traffic congestion. Wasting gas and time while waiting at a packed red light.

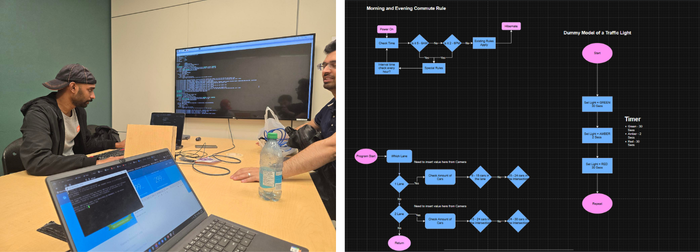

A group from the School for Advanced Digital Technology are tackling this everyday challenge by designing a traffic management system, using AI to manage traffic control.

To do so, they’ll need to create a database that includes logic for traffic control and connects the software with hardware (like traffic lights at multiple intersections). Once the database is populated, the system will be tested, then adjusted, using a physical diorama.

The goal is to stop traffic less frequently, reduce waiting at intersections and create more opportunities to cross or merge onto major roads.

Warren Fernandes explains how their funding will help them turn their vision into reality.

“A good percentage of our ISPF funding is used to source materials to build a scaled diorama of an intersection to properly display how the AI logic works. The materials include Arduino boards to control traffic lights, miniature traffic light LEDs, webcams that act as traffic cams, baseboards and planks for actual diorama construction and wiring.”

The School of Construction is also helping out with costs by offering to cut the group’s construction materials free of charge.

They also turn to their instructor, Shawn Simlik, for help on this project.

“He has been available for questions and has even provided recommendations on how to do the project more efficiently, in addition to providing us Raspberry Pi, an essential processor, early in our project,” Warren shares.

Feeding hungry livestock through affordable automations

Drive a half hour in any direction from Calgary’s downtown core, and you’ll find yourself on the edge of some of our province’s vast farmland. Alberta’s agricultural sector is central to the provincial economy, with cattle feeding and beef production representing nearly 40 per cent of farm revenues. But feeding this livestock isn’t always easy.

Many feedlots don’t have access to large-scale automation and continue to rely on outdated or manual feed preparation — a task that takes time, needs hands on deck and faces challenges like rising costs and labour shortages.

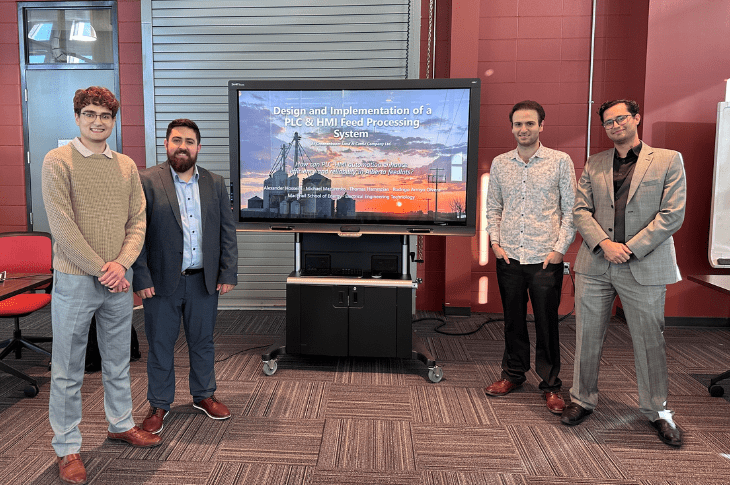

This team’s project applies industrial automation to this gap. Their goal is to design and implement a scaled-down, automated feed processing system to help smaller feedlots access cost-effective systems.

Team member Alexander Hosseini explains.

“Our ISPF funding was used to turn the Groenenboom feed mill design into a realistic working demo, rather than just a paper concept. It allowed us to create a prototype that physically replicated the grain-handling and feed-distribution steps on the lab bench, demonstrated how the system detects issues and shuts down safely, reflected real-world implementation and showed how grain moves through the system.”

They also mention strong support from their SAIT mentors throughout the project.

Their project advisor, Derek Tse, Instructor, MacPhail School of Energy, met with them weekly to keep the project on track. “He also brought his experience as an electrical engineering project manager to make sure our design decisions were realistic.”

Ilda Cronje, Instructor, Academic Services, advised them on how to communicate the project clearly for different audiences, including how to structure our report, poster and presentations so the technical content stays accessible.

Finally, “Shashi Persaud [Instructor, MacPhail School of Energy] kept us rigorous on the technical side by challenging our assumptions, checking our control logic and wiring approach and making sure the prototype stayed grounded in good industrial practice.”

Oki, Âba wathtech, Danit'ada, Tawnshi, Hello.

SAIT is located on the traditional territories of the Niitsitapi (Blackfoot) and the people of Treaty 7 which includes the Siksika, the Piikani, the Kainai, the Tsuut’ina and the Îyârhe Nakoda of Bearspaw, Chiniki and Goodstoney.

We are situated in an area the Blackfoot tribes traditionally called Moh’kinsstis, where the Bow River meets the Elbow River. We now call it the city of Calgary, which is also home to the Métis Nation of Alberta.