Environmental DNA lab looks for big answers in small places

Collecting snow tracks in the field for eDNA analysis

The Environmental DNA Research Lab in the MacPhail School of Energy #HereAtSAIT specializes in small. From tiny sample tubes to a nanopore sequencing device to the micro units of measurements used in analysis, such as microns and microliters.

The current research team is also small, with just two members, but the potential impact of their work is pretty big.

Colin Pattison, PhD, researcher and instructor, and Olivia Zamrykut, research assistant, are experimenting with collecting and analyzing environmental DNA, or eDNA — from animal fur, skin cells and waste found in water, the air and even spider webs — to identify what kinds of organisms are present in a natural area and understand how they interact.

“We’re looking at using an eDNA approach as a more efficient, safer and cost-effective way to do environmental monitoring and assessment work,” says Pattison.

These methods of sampling are more passive, allowing the team to explore biodiversity without actively disturbing wildlife or having to wait for an animal to make an appearance.

While an eDNA approach may not replace traditional monitoring and assessment methods entirely, Pattison and Zamrykut say it could help support conservation and environmental management while expediting impact assessments for infrastructure and development projects.

Olivia Zamrykut, research assistant, and Colin Pattison, PhD, researcher and instructor, MacPhail School of Energy.

DNA is everywhere

Most of the dust we find in our homes is made up of dead skin cells. Those cells contain DNA that identifies us as human.

In nature, thousands of different organisms leave behind their DNA every day.

💧Water sampling is one method for collecting eDNA Pattison and Zamrykut are testing.

“The water could come from a river, a pond or a lake,” says Pattison. “There are lots of different ways we can collect water samples and source DNA.”

Once gathered, the water samples are pumped through membrane filters with a very small pore size of 0.45 microns to capture the DNA.

✈️ If you see what looks like a foam airplane with no wings hanging from a tree in the woods, it might be there to collect eDNA.

“When the wind blows, it hits the side of the plane and turns the filter into the wind to capture material in the air.”

In the fall, Pattison and Zamrykut worked with students from SAIT’s Environmental Technology program to set up these special airplanes at two locations about 100 hectares each in Kananaskis.

🕸️A third collection method they’re testing uses spider webs.

“Instead of setting up equipment and waiting a few weeks, we wanted to test if we can go into the environment and collect eDNA from spider webs that are already there,” says Pattison.

“A group of Environmental Technology students are very interested in exploring this question for a capstone project.”

The capstone received funding from the Innovative Student Project Fund (ISPF) through SAIT’s Applied Research and Innovation Services hub.

So far, experiments with webs, water and air have all revealed detectable DNA consistent with wildlife the researchers know to be present in the area.

Starting from snow tracks

A recent graduate of SAIT’s Environmental Technology program, Zamrykut’s own capstone project was part of the eDNA lab’s origin story.

“We wanted to see if we could detect DNA in animal snow tracks,” she says. “We went out to Kananaskis, and Colin helped identify wolf, cougar and deer tracks,” she says. “My partner and I scooped as much snow as we could from each set of tracks and took our samples back to the lab.”

There, they extracted and sequenced the DNA and were able to confirm those animals made the tracks.

“It was a really exciting project.”

In addition to working at the lab, Zamrykut is currently completing a degree at the University of Manitoba.

Learning with nano tech

Although SAIT’s eDNA lab is relatively new, eDNA has been around for a few decades, explains Pattison.

“I've known about eDNA for about 10 years. I knew people were experimenting with it, and I wanted to bring it into the Environmental Technology program.

“One of the big things that’s changed over the last five to seven years is the ability to sequence DNA in a small lab like this one thanks to technology,” he says.

Before Zamrykut’s snow tracks project, Pattison would collect eDNA samples from the field and send everything to a lab for results.

“An outside lab would do the DNA extraction and sequencing, and they would tell us what we did or didn’t have in a report. I realized there wasn’t a whole lot of learning in that practice.”

Then, a colleague came across a nanosequencer.

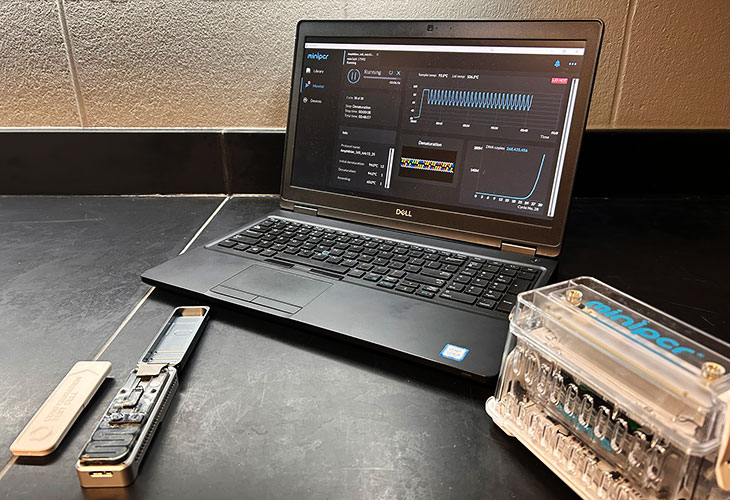

(Left) Nanosequencer: allows for real-time analysis of DNA and RNA sequences. (Right) Mini polymerase chain reaction machine: used to amplify small segments of DNA allowing researchers to analyze tiny quantities.

About the size of a granola bar, the device uses nanopores to sequence DNA. When a DNA molecule travels through a nanopore, it creates an electrical charge, which allows the device to determine the sequence of nucleotide bases and identify the species present in the sample.

“Everything we’re doing here now, started with the nanosequencer.”

Interdisciplinary learning and support

All research work conducted at the eDNA lab matches up with program coursework to encourage as much student involvement as possible.

In addition to the Environmental Technology ISPF capstone projects, two student groups from the Integrated Artificial Intelligence program are also working with the lab.

“We have a ton of data collected from remotely triggered cameras, as well as acoustic monitors,” says Pattison. “This data can tell us if what we're collecting from eDNA matches what we’re getting from the other instruments.”

The students are using AI to classify images and acoustic recordings by species, which will help save time and aid in animal identification.

“The acoustic monitoring data has all these layered sounds, for example, from a wetland,” says Zamrykut. “Dozens of different types of birds are singing and frogs are croaking all at the same time. Manually, it would take hours of just listening and, even then, we may not be able to pick out all the different species.”

SAIT’s eDNA lab is supported by funding to the MacPhail School of Energy from an anonymous donor. Pattison and Zamrykut are actively attending conferences to present their work while seeking out additional support.

“I think the lab is a great success story,” says Pattison. “Not only are we developing something that's brand new to SAIT, but we're doing it with one of our graduates, which is fantastic — and we still have so many plans.”

Oki, Âba wathtech, Danit'ada, Tawnshi, Hello.

SAIT is located on the traditional territories of the Niitsitapi (Blackfoot) and the people of Treaty 7 which includes the Siksika, the Piikani, the Kainai, the Tsuut’ina and the Îyârhe Nakoda of Bearspaw, Chiniki and Goodstoney.

We are situated in an area the Blackfoot tribes traditionally called Moh’kinsstis, where the Bow River meets the Elbow River. We now call it the city of Calgary, which is also home to the Métis Nation of Alberta.