"When people find out about my hobby, some find it fascinating; others just don’t get it,” says Arnel Lauranilla with a smile. “Some people own dogs; others have horses. I breed and race pigeons.”

Lauranilla (ACKP ’16) comes by his affection for animals honestly. As a ten-year-old boy in the Philippines, he helped his family take care of birds — including pigeons — as well as dogs, cats and rabbits.

But he didn’t learn about racing pigeons until moving to Calgary as an adult. After following and meeting with a local blogger who posts about the sport on YouTube, Lauranilla bought some birds and built a home for them — called a loft — in his backyard.

He followed strict municipal regulations and says, over five years, there have been no neighbour complaints. Today he has about 50 pigeons — not that many, compared to his fellow hobbyists. “Some have over a hundred,” he says.

“Pigeons that are bred for racing are different than wild pigeons you see around the city,” Lauranilla points out. “They are sleeker and more muscular, particularly in the wings and chest. You can tell a racing pigeon just by looking at it.”

Lauranilla is relatively new to a sport that goes back many centuries, possibly to ancient Egypt. Throughout history, and particularly during wartime, pigeons have been used to carry messages because of their ability to return home. Pigeon racing became a popular sport in Europe and immigrants eventually imported it to Canada. Calgary has one of the most active clubs in the country — the Calgary Racing Pigeon Club was established in 1904, eight years before the first Calgary Stampede.

Training the birds begins when they are fledglings. “I get up at 7 in the morning and let them out to fly for an hour,” Lauranilla says. “They get to know that when I whistle, it’s time to come home. Food and water bring them back. They know they’re safe in my loft.” Gradually, Lauranilla takes them further away with the goal of having them fly longer distances to make their way home.

The night before a race, Lauranilla brings his birds to the northeast Calgary clubhouse, where they are tagged and registered. Early the next morning, a driver will take the pigeons far out of town — often hundreds of kilometres — to be released. Lauranilla and his fellow racers hang out, eat pizza, talk birds and then head home to wait. The first bird to return to its loft is the winner.

“I sit in my yard and wait,” says Lauranilla. “Sometimes they don’t come home. Some are killed by natural predators, some run into powerlines, some just fly away. One of my birds came in second place. That’s the best so far.”

Lauranilla says his wife teases him about spending so much time with his birds. A busy cook with Carewest, Lauranilla says time with his pigeons “is like therapy.”

And, he says, it’s an interest he’s noticed his 10-year-old son, Liam, seems to share. “He visits the loft,” says Lauranilla, “and sometimes we go to the clubhouse together on race days.”

THROUGH THE LENS

OF SAIT ALUMNI

Almost every weekend from early May to late September, Arnel Lauranilla and his fellow Calgary Pigeon Racing Club (CPRC) members race their specially trained pigeons over distances ranging from 100 to 500 miles.

In late August, LINK asked two SAIT alumni — photojournalists Leah Hennel (JA ’98) and Rob Olson (JA ’98) — to create a photo gallery documenting each stage in a race, from basketing to liberation to the thrill of the pigeons returning home.

FRIDAY, 7 PM

The night before each race, club members place the pigeons they will be racing in baskets built to keep them calm and secure.

As members bring their baskets to the CPRC’s clubhouse in northeast Calgary, the soft sound of cooing fills the air. Leah Hennel photographs the action and club members chat about strategy — particularly important because tomorrow’s race is for young birds less than six months old. For many of these fledglings, it’s their first-ever race.

FRIDAY, 7:30 PM

Once everyone has arrived, the process of basketing begins. Each bird is removed from its crate and registered by being placed on an electronic touchpad. It scans a light electronic band placed on each bird’s leg. Every CPRC member has a mini-computer used to track their own birds.

The pigeon is then placed in an aluminum release cage, with owners carefully marking the top of each crate to ensure it holds no more than 25 pigeons. Inside, dividers help keep the birds separated and stress-free, with good air ventilation to keep them comfortable.

FRIDAY, 8 PM

The club works together like a well-oiled machine. Every member has a job and soon basketing is complete, the crates are loaded on a specially designed truck, and the pigeons are ready to nest for the night as they travel to the release location. For this race, that location is Tilley, Alberta (southeast of Brooks).

To capture the start of the actual race, Lethbridge photographer Rob Olson got up at 4 am and travelled to the baseball diamonds just outside Tilley. That’s where the birds were released from their crates — a process called liberation in pigeon racing terms.

SATURDAY, 7 AM

As the sun comes up on a cloudy day, the club’s driver scans the sky. Pigeons can’t race if it’s raining, but luckily the weather co-operates and the liberation can begin.

One by one, the side doors of each crate swings open. By 7:05 am, every pigeon is on its way, following that mysterious homing instinct (which some research says is linked to magnetic fields).

Pigeons often fly the majority of a race in groups, drafting one another the same way cycling teams do to conserve energy. Average speed for a racing pigeon is about 50 miles per hour, but with a good tailwind some can easily travel at 65 mph. Pigeons with a mate waiting at their loft will fly faster to get home.

SATURDAY, 10 AM

Back in Calgary, Arnel and his son Liam set up lawn chairs in their backyard, waiting for Arnel’s pigeons to return to his A-L Loft. Many racers learn the sport from parents and other family members, and often children grow up helping to care for the pigeons.

For this 100-mile race, it takes the birds an average of four hours to fly home from Tilley. That’s a bit slower than normal, but these are young birds and there are strong headwinds this morning.

When the pigeons return, they land on a small touchpad at the entrance to their loft. It scans their electronic leg band and records the time they arrive.

“Then they get inside right away because they are hungry or thirsty,” Arnel says. “That’s part of what motivates them to fly home right away.”

He describes the feeling of seeing his pigeons descend from the sky as incomparable. “It’s just so exciting, every single time,” he says. “It’s hard to put into words.”

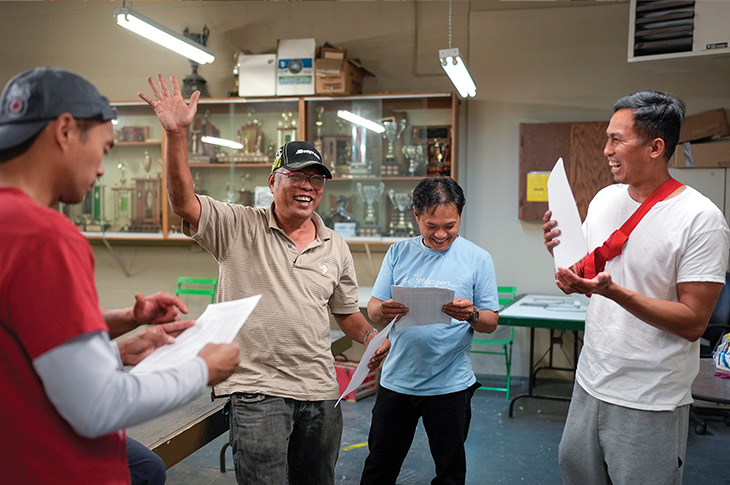

MONDAY, 7 PM

Club members gather once again at the clubhouse, bringing along their handheld digital trackers. Dave McKop (below, left) uses the TauRIS tracking system — one of the world’s leading electronic clocking systems for pigeon racing — to upload data and tally race results.

There is no prize money in pigeon racing; all racing fees go towards running the club. Winning is purely for fun, and racing is for the sense of fellowship and the love of pigeon sport.

Want to learn more about pigeon racing? Visit the club's website at calgarypicgeonracing.ca.

Like what you are reading?

Find more stories from past, present and upcoming issues of LINK magazine!

Oki, Âba wathtech, Danit'ada, Tawnshi, Hello.

SAIT is located on the traditional territories of the Niitsitapi (Blackfoot) and the people of Treaty 7 which includes the Siksika, the Piikani, the Kainai, the Tsuut’ina and the Îyârhe Nakoda of Bearspaw, Chiniki and Goodstoney.

We are situated in an area the Blackfoot tribes traditionally called Moh’kinsstis, where the Bow River meets the Elbow River. We now call it the city of Calgary, which is also home to the Métis Nation of Alberta.